Is drinking at any level okay?

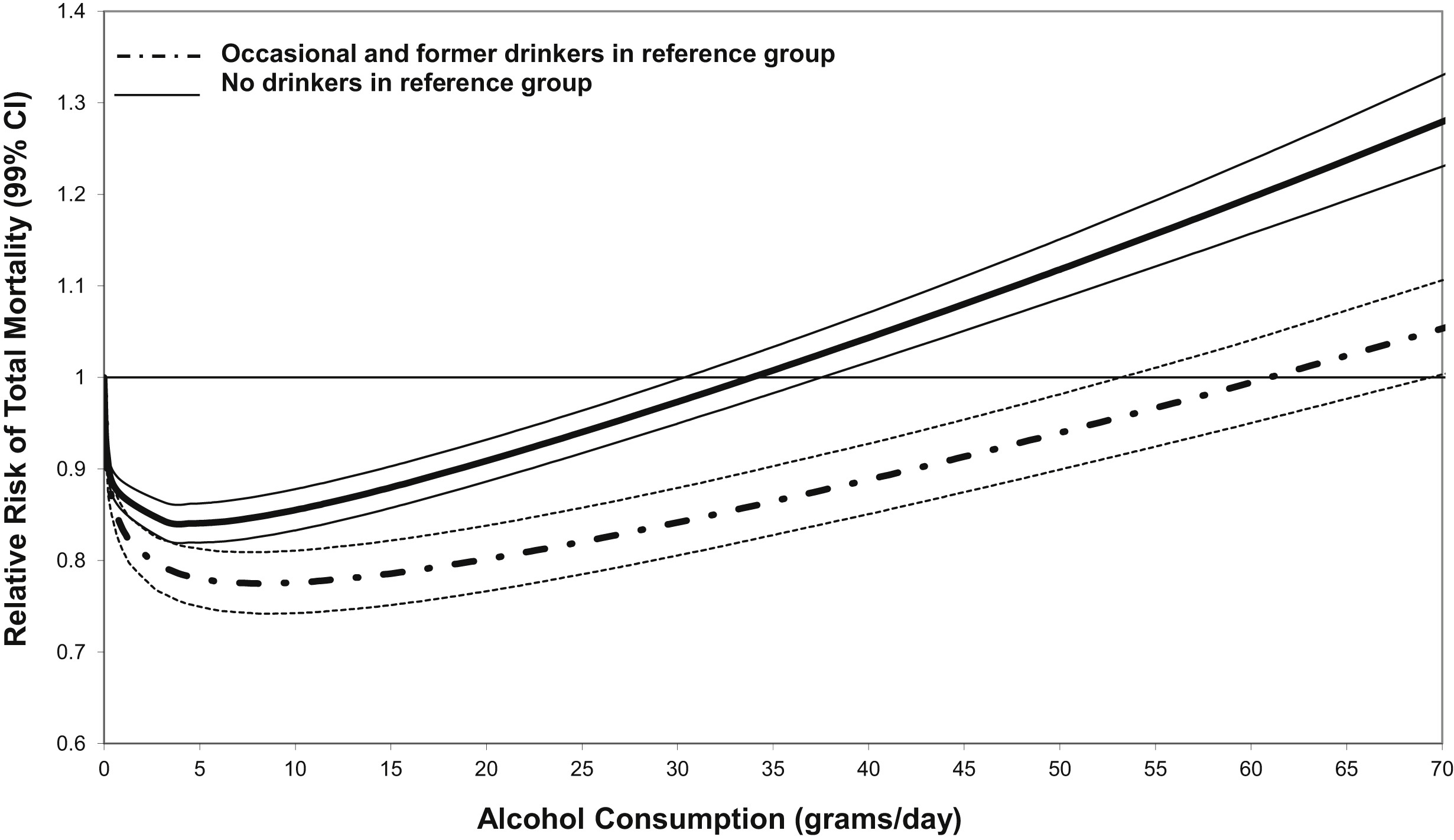

Alcohol consumption at any level remains deeply controversial. Many researchers argue for the ‘J-shaped curve’. Accordingly, low to moderate consumption of alcohol is viewed as beneficial while excessive drinking remains harmful.

However, this view has suffered from recent sustained attack. Vested interests from the alcohol industry are of particular concern. Such interests can potentially sway research conclusions to favour recommending moderate use of alcohol. Indeed, these researchers have suggested we rethink our use of the phrase ‘harmful effects of alcohol’ because it implies there are notable benefits as well.

Other concerns relate to the finer points of research methodology. When undertaking public health research relating to alcohol consumption, are we attracting a balanced and unbiased group of people? Or are we unintentionally biasing our research findings by recruiting a group of people who drink moderately, but are also more healthy overall? This debate is very far from being reconciled.

So what is a standard drink?

What really is a standard drink? According to the Queensland government website standard serve of alcohol is defined as containing 10 grams of alcohol. Although the actual amount varies by alcohol volume, a typical standard serve of beer is 260ml (4.8% alcohol volume or full strength) or 100ml of red wine (13%).

However, when we look at the J-shaped curve, the benefits of moderate alcohol use peak at just 5 grams of alcohol. Accordingly, this is really only half a beer or 50ml of wine.

In my experience, most people are quite shocked at just how little a standard serve of alcohol actually is. This is often compared with most people’s usual pour of wine after work, that is often 2 – 3 times the recommended standard serve.

What are the reasons most commonly reported?

There are myriad reasons why people drink. When drinking in moderation – defined as less than 2 standard drinks per day for men, and less than 1 standard drink for women, health implications are rarely an issue. Increasingly however, people are seeking counselling when their drinking levels become problematic. These problems typically come in the form of changes to behaviour (aggressive or sexualised as two commonly reported examples) or when language becomes unfiltered, and friends and loved ones become the target of attack.

Reason #1: Pain

The most commonly reported pattern of drinking involves the management of physical or emotional stress and pain. Drinking can often become habitual or ritualised, especially when encouraged as part of social bonding with peers. This pattern of drinking can also quickly escalate under social pressures. Patients often report not being able to monitor or regulate their alcohol intake as well when surrounded by friends.

There is often the perception of a trap too: I can’t really afford the time off to manage my health complaints, so I just have to keep on going.

Stress can also be a huge trigger for drinking. Patients often report feeling a weight being lifted after a few drinks. However this is often only temporary, and can even make matters worse, when drinking becomes excessive, and other outcomes ensue. In contrast to physical pain, stress and emotional pain often remain unacknowledged. There remains an uncomfortable stigma around mental health issues amongst certain sections of the community with drinking, ironically, often seen as a more appropriate treatment.

Reason #2: Enjoyment

The next most common pattern of drinking is strongly associated with social circumstances. “I really don’t drink much most of the time; but when I go out…”. A number of factors seem to be at play here. These can include a discomfort with large groups of people, encouragement by peers, or even the environment (favourite pub/bar) and timing (end of the week).

However, this pattern of drinking can often prove the most dangerous. This is especially true when patients report drinking excessively on one night of the week – a pattern of binge drinking. Of particular concern is when blackouts are common outcomes of the evening. These are often justified in terms of having the week to recover. However, we know that the health implications of such experiences can be catastrophic.

Reason #3: Punishment

This pattern of drinking often occurs in secret, either at home, or remaining carefully hidden behind a veneer of professional competence. Accordingly, this pattern of drinking often emerges only when loss of employment or relationship occurs.

Patients often describe a sense of ‘not deserving’. This often comes in the form of negative and highly critical thoughts that aim at demoralising and eroding self-worth. Losses are all too often viewed as self-fulling prophecies: I didn’t deserve success, therefore I lost my job, partner.

Often associated with punishment is the notion of transgression. ‘I’ve gotten away with it for this long’, or ‘no-one will notice’ are common statements. This also often goes hand in hand with isolation. Meaningful relationships often prove elusive when motivated by punishment and transgression.

Reason #4: Ritual

Patients have reported witnessing close family members drinking routinely in their childhood. “Mum would pour herself a whiskey at 5pm on the dot”, or “dad would have a few beers of a Friday evening”. As a form of identification, these patterns of drinking are adopted as part of becoming an adult. Patients often refer to ‘happy times’, where alcohol consumption was associated with family cohesion. However, this pattern of behaviour can also lead into any of the above categories.

Conclusion

This is by no means a conclusive list. However, it does reflect a substantial number of reasons actually reported by patients in counselling.

Effective treatment does not mean challenging maladaptive thoughts and behaviours. Rather, in my experience, effective treatment means listening to the unique stories and life circumstances of patients. Almost universally, it is discussion of historical events that alter current behaviours. Patients often return to troubling experiences that remain either irreconciled or incomprehensible. These two dimensions all too often remain the cornerstones of addiction and interestingly trauma. I have written elsewhere about how traumatic events can become encoded in the unconscious.

Should you read this post and identify with any of this discussion, I’d encourage you to seek out the assistance of someone who is professional, trustworthy and compassionate.

Recent Comments